Ben-Hur (1959 film)

| Ben-Hur | |

|---|---|

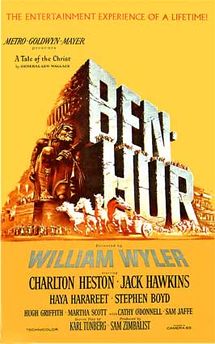

film poster by Reynold Brown |

|

| Directed by | William Wyler |

| Produced by | Sam Zimbalist |

| Written by | Karl Tunberg Lew Wallace (Novel) Uncredited: Gore Vidal Christopher Fry |

| Starring | Charlton Heston Jack Hawkins Haya Harareet Stephen Boyd Hugh Griffith |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

| Cinematography | Robert L. Surtees |

| Editing by | John D. Dunning Ralph E. Winters |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Warner Bros. (Collecters Edition) |

| Release date(s) | November 18, 1959 |

| Running time | 212 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Gross revenue | $90,000,000 |

Ben-Hur (or Benhur) is a 1959 epic film directed by William Wyler, the third film version of Lew Wallace's 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. It premiered at Loew's State Theatre in New York City on November 18, 1959. The film went on to win a record of eleven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, a feat equaled only by Titanic and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

Contents |

Plot

The film's prologue depicts the traditional story of the Nativity of Jesus Christ.

In AD 26, Prince Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) is a wealthy Jewish merchant in Jerusalem. His childhood friend Messala (Stephen Boyd), now a Roman military tribune, arrives as the new commanding officer of the Roman garrison. Judah and Messala are happy to reunite after years apart, but politics divide them; Messala believes in the glory of Rome and its imperial power, while Judah is devoted to his faith and the freedom of the Jewish people. Messala asks Judea for names of Jews who criticize the Roman government; Judah counsels his countrymen against rebellion but refuses to name names, and the two part in anger.

Judah, his mother Miriam (Martha Scott), and sister Tirzah (Cathy O'Donnell) welcome their loyal slave Simonides (Sam Jaffe) and his daughter Esther (Haya Harareet), who is preparing for an arranged marriage. Judah gives Esther her freedom as a wedding present, and the two realize they are attracted to each other.

During the parade for new governor of Judea Valerius Gratus, a tile falls from the roof of Judah's house and startles the governor's horse, which throws Gratus off, nearly killing him. Although Messala knows it was an accident, he condemns Judea to the galleys, and imprisons his mother and sister to intimidate the restive Jewish populace by punishing the family of a known friend and prominent citizen. Judah swears to return and take revenge. En route to the sea, he is denied water when his slave gang arrives at Nazareth. He collapses in despair, but a local carpenter named Jesus gives him water and renews his will to survive.

After three years as a galley slave, Judah is assigned to the flagship of Consul Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), tasked to destroy a fleet of Macedonian pirates. The commander notices the slave's self-discipline and resolve and offers to train him as a gladiator or charioteer, but he declines, declaring that God will aid him.

As Arrius prepares for battle, he orders the rowers chained but Judah to be left free. Arrius's galley is rammed and sunk, but Judah unchains other rowers, escapes and saves Arrius's life and, since Arrius believes the battle ended in defeat, prevents him from committing suicide. Arrius is credited with the Roman fleet's victory, and in gratitude petitions Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (George Relph) to drop all charges against Judah, adopting him as his son. With regained freedom and wealth, Judah learns Roman ways and becomes a champion charioteer, but longs for his family and homeland.

While returning to Judea, Judah meets Balthasar (Finlay Currie) and his host, Arab sheik Ilderim (Hugh Griffith), who owns four magnificent white Arabian horses. Ilderim introduces Judah to his "children" and asks him to drive Ilderim's quadriga in the upcoming race before the new Judean governor, Pontius Pilate (Frank Thring). He declines, but hears that champion charioteer Messala will compete; as Ilderim observes, "There is no law in the arena. Many are killed."

Judah learns that Esther's arranged marriage did not occur and that she is still in love with him. He visits Messala and demands that he free his mother and sister, but the Romans discover that Miriam and Tirzah have contracted leprosy and expel them from the city. They beg Esther to conceal their condition from Judah, so she tells him that his mother and sister have died in prison.

Judah enters the race. Messala drives a "Greek chariot," with blades on the hubs, designed to tear apart competing chariots. In the violent and grueling race, he attempts to destroy Judah's chariot but destroys his own instead; Messala is trampled and almost killed, while Judah wins the race. Before dying, Messala tells Judea that the race is not over; he can find his mother and sister in the "Valley of the Lepers, if you can recognize them."

The film is subtitled "A Tale of the Christ", and it is at this point that Jesus Christ reappears. Esther is moved by the Sermon on the Mount. She tells Judea about it, but he will not be consoled; blaming Roman rule — not Messala — for his family's fate, Judea rejects his patrimony and citizenship, and plans violence against the Empire. Learning that Tirzah is dying, Judea and Esther take her and Miriam to see Jesus, but they cannot get near him; his trial has begun, with Pilate washing his hands of responsibility for his fate. Recognizing Jesus from their earlier meeting, Ben-Hur attempts to give him water during his march to Calvary but guards pull them apart.

Judea witnesses the Crucifixion. Miriam and Tirzah are healed by a miracle, as are Judea's heart and soul. He tells Esther that as he heard Jesus talk of forgiveness while on the cross, "I felt His voice take the sword out of my hand." The film ends with the empty crosses of Calvary and a shepherd and his flock.

Cast

- Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur, alias Quintus Arrius the Younger

- Stephen Boyd as Messala

- Martha Scott as Miriam

- Cathy O'Donnell as Tirzah Bat-Hur

- Haya Harareet as Esther Bat-Simonides

- Sam Jaffe as Simonides

- Jack Hawkins as Quintus Arrius

- Terence Longdon as Drusus

- Hugh Griffith as Sheik Ilderim

- Frank Thring as Pontius Pilate

- Claude Heater (uncredited) as Jesus

- Marina Berti as Flavia

- Jose Greci (uncredited) as Mary

- Laurence Payne (uncredited) as Joseph

- Richard Hale (uncredited) as Gaspar

- Reginald Lal Singh as Melchior

- Michael Dugan (uncredited) as a seaman

- Finlay Currie as Balthasar/Narrator

Music

- Shofar Calls (Star of Bethlehem Disappears) - man

- Love Theme — MGM Studio and Orchestra

- Fertility Dance — Indians, MGM Studio and Orchestra

- Arrius' Party — MGM Studio and Orchestra

- Hallelujah (Finale) - MGM Studio and Orchestra Chorus

The film score was composed and conducted by Miklós Rózsa, who scored most of MGM's epics. Rózsa won his third Academy Award for his work on the film. The soundtrack is one of the most popular motion picture scores ever written, and is listed on the AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores.

Stunts

- Michael Dugan (I)

- Glenn Randall jr

- Yakima Canutt

- Sounder Raj

Production

Financing

Ben-Hur was an extremely expensive production, requiring 300 sets scattered over 340 acres (1.4 km²). The $15 million production was a gamble made by MGM to save itself from bankruptcy; the gamble paid off when it earned a total of $90 million worldwide.

Aspect ratio

The movie was filmed in a process known as "MGM Camera 65", 65 mm negative stock from which was made a 70 mm anamorphic print with an aspect ratio of 2.76:1, one of the widest prints ever made, having a width of almost three times its height. An anamorphic lens which produced a 1.25X compression was used along with a 65 mm negative (whose normal aspect ratio was 2.20:1) to produce this extremely wide aspect ratio. This allowed for spectacular panoramic shots in addition to six-channel audio. In practice, however, "Camera 65" prints were shown in an aspect ratio of 2.5:1 on most screens, so that theaters were not required to install new, wider screens or use less than the full height of screens already installed.

Casting and acting

Many other men were offered the role of Ben-Hur before Charlton Heston. Burt Lancaster claimed he turned down the role of Ben-Hur because he "didn't like the violent morals in the story". Paul Newman turned it down because he said he didn't have the legs to wear a tunic. Rock Hudson and Leslie Nielsen were also offered the role.

Out of respect, and consistent with Lew Wallace's stated preference, the face of Jesus is barely shown. He was played by opera singer Claude Heater, who received no credit for his only film role.

In an interview for the 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, screenwriter Gore Vidal asserts that he persuaded Wyler to direct Stephen Boyd to create a veiled homoerotic subtext between Messala and Ben-Hur. Vidal says he wanted to help explain Messala's extreme reaction to Ben-Hur's refusal to name his fellow Jews to a Roman officer, and suggested to Wyler that Messala and Ben-Hur had been homosexual lovers while growing up, but that Ben-Hur was no longer interested, so that Messala's vindictiveness would be motivated by his feeling of rejection. Since the Hollywood production code would not permit this, the idea would have to be implied by the actors, and Vidal suggested to Wyler that he direct Stephen Boyd to play the role that way, but not tell Heston. Vidal claims that Wyler took his advice, and that the results can be seen in the film.

Galley sequence

The original design for the boat Ben-Hur is enslaved upon was so heavy that it couldn't float. The scene therefore had to be filmed in a studio, but another problem remained: the cameras didn't fit inside, so the boat was cut in half and made able to be wider or shorter on demand. The next problem was that the oars were too long, so those were cut too; however, this made it look unrealistic, because the oars were too easy to row; so weights were added to the ends.

During filming, director Wyler noticed that one of the extras was missing a hand. He had the man's stump covered in false blood, with a false bone protruding from it, to add realism to the scene when the galley is rammed. Wyler made similar use of another extra who was missing a foot.

The galley sequence includes the successive commands from Arrius, “Battle speed, Hortator... Attack speed... Ramming speed!” The word hortator is no longer in use, and is notably absent from most modern dictionaries. It was a Latin word that on a ship meant “chief of the rowers”, or “he who has command over the rowers”,[1] and likely has roots in the Latin verb hortor (“to exhort, encourage”). The command "Ramming speed, Hortator!", which is widely remembered and parodied, never occurs.

The galley sequence is purely fictional, as the Roman navy, in contrast to its early modern counterparts, did not employ convicts as galley slaves.[2]

Chariot race

The chariot race in Ben-Hur was directed by Andrew Marton, a Hollywood director who often acted as second unit director on other people's films. Even by current standards, it is considered to be one of the most spectacular action sequences ever filmed. Filmed at Cinecittà Studios outside Rome long before the advent of computer-generated effects, it took over three months to complete, using 15,000 extras on the largest film set ever built, some 18 acres (73,000 m2). Eighteen chariots were built, with half being used for practice. The race took five weeks to film. Tour buses visited the set every hour.

The section in the middle of the circus, the spina, is a known feature of circuses, although its size may be exaggerated to aid filmmaking. The golden dolphin lap counter was a feature of the Circus Maximus in Rome.

Charlton Heston spent four weeks learning how to drive a chariot. He was taught by the stunt crew, who offered to teach the entire cast, but Heston and Boyd were the only ones who took them up on the offer (Boyd had to learn in just two weeks, due to his late casting). At the beginning of the chariot race, Heston shook the reins and nothing happened; Aldebaran, Altaïr, Antares and Rigel, the four horses named after stars, remained motionless. Finally someone way up on top of the set yelled, "Giddy-up!" The horses then roared into action, and Heston was flung backward off the chariot.

To give the scene more impact and realism, three lifelike dummies were placed at key points in the race to give the appearance of men being run over by chariots. Most notable is the stand-in dummy for Stephen Boyd's Messala that gets tangled up under the horses, getting battered by their hooves. This resulted in one of the most grisly fatal injuries in motion picture history up until then, and shocked audiences.

There are several urban legends surrounding the chariot sequence, one of which states that a stuntman died during filming. Stuntman Nosher Powell claims in his autobiography, "We had a stunt man killed in the third week, and it happened right in front of me. You saw it, too, because the cameras kept turning and it's in the movie".[3] There is no conclusive evidence to back up Powell's claim and it has been adamantly denied by director William Wyler, who states that neither man nor horse was injured in the famous scene. The movie's stunt director, Yakima Canutt, stated that no serious injuries or deaths occurred during filming.[4]

Another urban legend states that a red Ferrari can be seen during the chariot race; the book Movie Mistakes claims this is a myth.[5] (Heston, in the DVD commentary track, mentions a third urban legend that is not true: That he wore a wristwatch. He points out that he was wearing leather bracers right up to the elbow.)

However, one of the best-remembered moments in the race came from a near-fatal accident. When Judah's chariot jumps another chariot which has crashed in its path, the charioteer is seen to be almost thrown from his mount and only just manages to hang on and climb back in to continue the race. In reality, while the jump was planned, the character being flipped into the air was not planned, and stuntman Joe Canutt, son of stunt director Yakima Canutt, was considered fortunate to escape with only a minor chin injury. Nonetheless, when director Wyler intercut the long shot of Canutt's leap with a close-up of Heston clambering back into his chariot, a memorable scene resulted.[6]

Differences between novel and film

There are several differences between the original novel and the film. The changes made serve to make the film's storyline more immediately dramatic.

- In the novel, Messala is seriously, but not fatally, injured in the chariot race. In the movie, Messala falls victim to an accident that is caused by his own attempts to sabotage Ben-Hur, and he dies from the wounds sustained from the accident. In the book, Messala plots to have Ben-Hur murdered in revenge, but his plans go awry. It is revealed at the end of the novel that Iras (who is Messala's mistress and does not appear in the 1959 film) had murdered Messala in a fit of anger about five years after the chariot race.

- The film has the chariot race taking place in Jerusalem, the novel however has it taking place in Antioch.

- In the novel, Ben-Hur becomes a convert to Christianity before, rather than after, the Crucifixion, and he does not display the harsh bitterness that he does in the William Wyler film. Similarly, the healing of Ben-Hur's mother and sister takes place earlier in the book, not immediately after the death of Christ.

- In the novel, the character of Quintus Arrius was acquainted with Ben-Hur's father, but in the movie there was no such prior association between the Arrius and Hur families. In the novel, Arrius dies and passes his property and title on to Ben-Hur prior to Ben-Hur's return home. No mention of Arrius's death is made in the 1959 film, so presumably he is still alive at film's end.

- The novel ends about 30 years after the chariot race, with the Ben-Hur family living in Misenum, Italy. While in Antioch Ben-Hur learns that Sheik Ilderim (who does not die in any of the film versions of the novel) had bequeathed him a large amount of money. At about the same time he learns of the persecution of Christians in Rome by Emperor Nero, Ben-Hur helps establish the Catacomb of San Calixto so that the Christian community will have a place to worship freely. The movie however ends almost immediately after the Crucifixion of Christ and the healing of Ben-Hur's mother and sister.

Box office performance

Ben-Hur earned $17,300,000.[7]

Awards and honors

The film won an unprecedented 11 Academy Awards, a number matched only by Titanic in 1998 and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2004.

- Best Motion Picture;

- Best Director for William Wyler;

- Best Leading Actor for Charlton Heston;

- Best Supporting Actor for Hugh Griffith;

- Best Set Decoration, Color for Edward C. Carfagno, William A. Horning, and Hugh Hunt;

- Best Cinematography, Color;

- Best Costume Design, Color;

- Best Special Effects;

- Best Film Editing for John D. Dunning and Ralph E. Winters;

- Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture; and

- Best Sound.

Additionally, the film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

The film also won four Golden Globe Awards: Best Motion Picture, Drama, Best Motion Picture Director, Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture for Stephen Boyd, and a Special Award to Andrew Marton for directing the chariot race sequence. It won the BAFTA Award for Best Film, the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Picture and the DGA award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in a Motion Picture.

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #72

- 2001 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills #49

- 2005 AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores #21

- 2006 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers #56

- 2007 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #100

- 2008 AFI's 10 Top 10 #2 Epic film

Ben-Hur also appeared in Empire magazine's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time where it ranked at number 491.[8]

The Library of Congress added Ben-Hur for preservation into the National Film Registry in 2004.

First telecast

The film's first telecast took place on Sunday, February 14, 1971 [9]. The film was shown in full-screen pan and scan format, as a prime time network television special on CBS. Because of the film's length, the entire evening's regular CBS lineup, beginning with 60 Minutes, was scrapped for just that one night, one of the few times in the history of CBS that 60 Minutes was preempted for a movie special. The commercials forced a five-hour running time on the film, which was shown between 7:00 P.M. and 12:00 A.M., E.S.T.

DVD release

Ben-Hur has been released to DVD on three occasions. The first was on March 13, 2001 as a one-disc widescreen release, the second on September 13, 2005 as a four-disc set, and the third as part of the Warner Bros. Deluxe Series.

2001 release

(2-Disc release in some countries, a 2 sided disc in the U.S.) Disc One & Two: The Movie + Extras

- Subtitles: English, Spanish, French

- Audio Tracks: English (Dolby Digital 5.1)

- Commentary by: Charlton Heston

- Documentary Ben-Hur: The Making of an Epic

- Newly discovered screen tests of the final and near-final cast including Leslie Nielsen, Cesare Danova, and Haya Harareet

- Addition of the seldom-heard Overture and Entr'acte music

- On-the-set photo gallery featuring Wyler, producer Sam Zimbalist, cameraman Robert Surtees, and others

2005 release

(4-Disc) Discs One & Two: The Movie

- Newly Remastered and Restored from Original 65–mm Film Elements

- Dolby Digital 5.1 Audio

- Commentary by Film Historian T. Gene Hatcher with Scene Specific Comments from Charlton Heston

- Music-Only Track Showcasing Miklós Rózsa's Score (only available on Region 1 editions, even though on other Region releases it was advertised on cover, it is absent in those regions)

Disc Three: The 1925 Silent Version

- The Thames Television Restoration with Stereophonic Orchestral Score by Composer Carl Davis

Disc Four: About the Movies

- New Documentary: Ben-Hur: The Epic That Changed Cinema—Current filmmakers, such as Ridley Scott and George Lucas, reflect on the importance and influence of the film

- 1994 Documentary: Ben-Hur: The Making of an Epic, hosted by Christopher Plummer

- Ben-Hur: A Journey Through Pictures—New audiovisual recreation of the film via stills, storyboards, sketches, music and dialogue

- Screen Tests

- Vintage Newsreels Gallery

- Highlights from the 1960 Academy Awards Ceremony

- Trailer Gallery

Also Included in paperback form

- 36 page booklet about the production

References

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=hU8MAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA344&dq=hortator

- ↑ Casson, Lionel (1971). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Nosher Powell (2001). Nosher!: p.254

- ↑ Canutt, Yakima; Drake, Oliver. "Stunt Man: The Autobiography of Yakima Canutt, Chapter 1: The Race to Beat"(1979)

- ↑ Sandys, John (2002, 2005). Movie Mistakes Take 4: p.5

- ↑ Canutt, Yakima; Drake, Oliver. "Stunt Man: The Autobiography of Yakima Canutt" (1979) p. 16-19

- ↑ Steinberg, Cobbett (1980). Film Facts. New York: Facts on File, Inc.. p. 23. ISBN 0-87196-313-2. When a film is released late in a calendar year (October to December), its income is reported in the following year's compendium, unless the film made a particularly fast impact (p. 17)

- ↑ http://www.empireonline.com/500/1.asp

- ↑ http://www.brainyhistory.com/events/1971/february_14_1971_140094.html

Further reading

- "Charlton Heston: An Incredible Life: Revised Edition" Michelel Bernier, Createspace, 2009

External links

- Ben-Hur (1959) at the Internet Movie Database

- Getting It Right the Second Time — a comparative analysis of the novel, the 1925 film, and the 1959 film, at BrightLightsFilm.com

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||